The Indigenous people called “Abenaki” have continuously lived in Northeastern North America, in the homelands they call “Ndakinna,” for more than 12,000 years. They have survived and adapted to drastic environmental changes since the “Ice Age” era, when glaciers covered the land. Over time, as the glaciers melted, the region changed from arctic tundra to eventually become the forested lands of present-day Vermont. The area was rich in natural resources, and people moved seasonally around Ndakinna to utilize various hunting territories and gathering places, many of which were occupied for several thousand years.

Long before European arrival and into the present day, Abenaki people maintained social, economic, and political relationships with other Indigenous people. Some relationships were friendly, marked by trade and alliance, but some were adversarial when resources were at stake. Abenaki family band organization was fluid and flexible, and people routinely sought marriage partners in other bands or tribes. The complexity of relationships between Abenaki people and their neighbors continues into the present day.

Before European contact, these people called themselves Wôbanakiak, a name that combines the terms for dawn (wôban) and land (aki) with an animate plural ending (-ak), meaning people “from where the daylight comes” (Laurent, 1884, p. 205). During the mid-1600s, European colonial settlers began using the name “Abenaki” or “Wabanaki” to apply to many different Native American communities, tribes, family bands, and groups across New England (Charest, 2001; Day, 1978; Day, 1981; Fabvre, 1970).

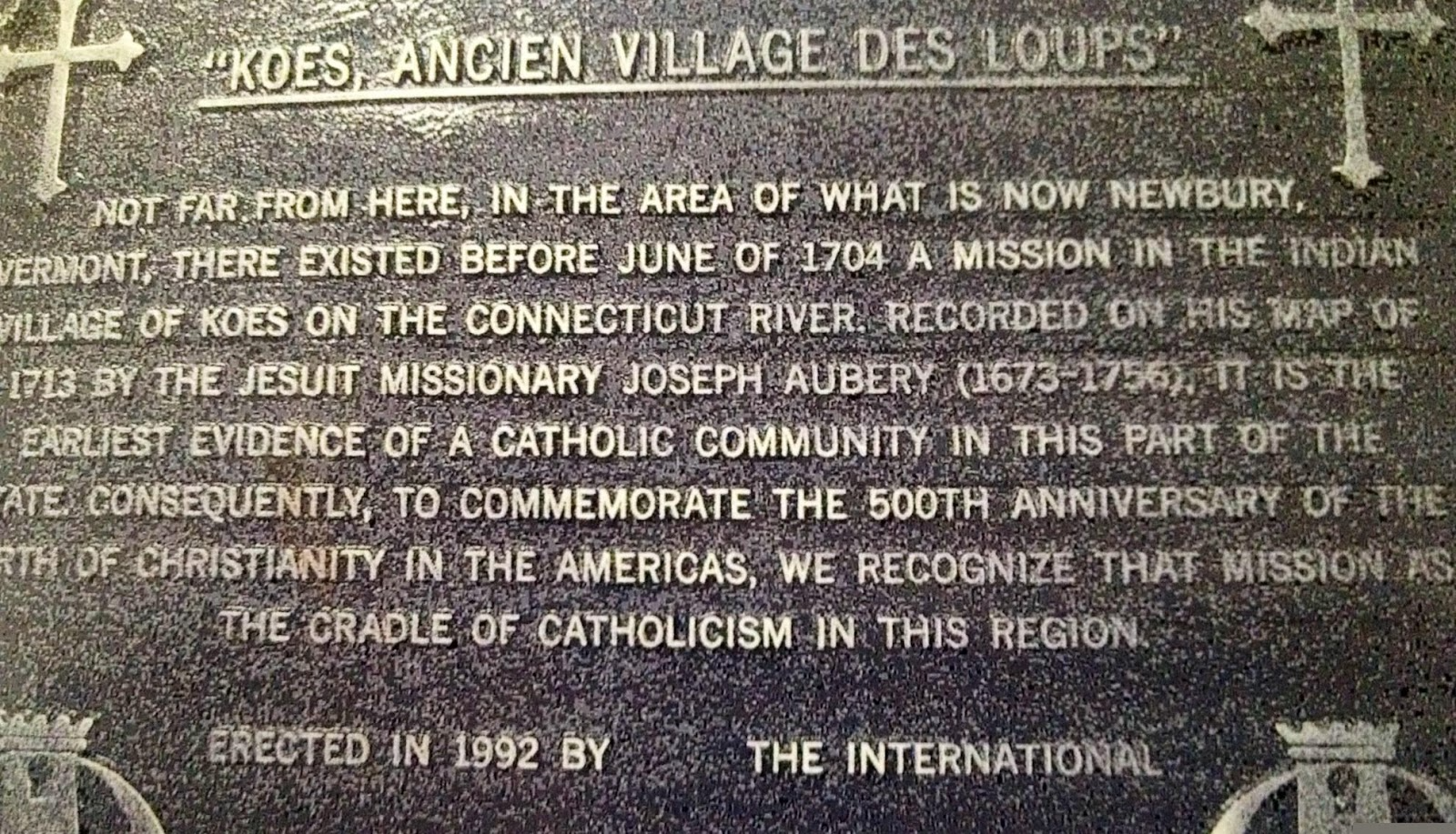

By the late 1600s, French Jesuit missionaries convinced some Abenaki families to relocate to Catholic missions on regional waterways. These included the St. Francis Mission on the St. Lawrence River; Fort Saint-Frédéric on Lake Champlain; and Mission des Loups on the upper Connecticut River, among others. The French built another mission along the Missisquoi River in the mid-1700s. Some Abenaki families embraced mission life and French allies, but others rejected the restrictions imposed by French colonists and missionaries, and returned to their original territories. Clashes between French and English settlers during the “French and Indian War” era in the early to mid-1700s led to the burning of these missions.

Historical marker commemorating the Koas Mission des Loups. Photo by Chief Nancy Milette Doucet. Courtesy, Koasek Traditional Band of the Koas Abenaki Nation.

According to the scholar Gordon Day, who worked closely with the community of Odanak in Quebec during the mid-1900s, families from many different tribal groups in central and northern New England sought refuge at the St. Francis Mission on the St. Lawrence River during the chaos of the French and Indian wars (Day, 1981). Some of the families living at Odanak today are descendants of these refugees. Many Abenaki families in Cowass and Missisquoi territory, however, refused French invitations to relocate to Quebec (Calloway, 1991, p.152).

Over the years, Abenaki families made individual decisions about where to live. Some went to Odanak and stayed; others never left their original home places in present-day Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine. Some families crossed the St. Lawrence seasonally, and returned to living in familiar homelands (Parker, 1994).

Traditionally, Abenaki bands identified themselves by the place names of particular regions in Ndakinna, such as Cowass, Missisquoi, Pennacook, etc. But over time, the Abenaki (like many other Native American tribes and communities on the North American continent) have come to be known, not by their own names, but by names assigned by government officials in the states, provinces, and nations that surround them.

Abenaki people in the United States and Canada continue to have different experiences. In the United States, Abenaki people can hold dual citizenship as U.S. citizens and as Indigenous people. In 2011 and 2012, the State of Vermont formally granted state recognition to four resident Abenaki tribes (Elnu, Koasek, Missisquoi, and Nulhegan) with over 6,000 Abenaki citizens. In Canada, tribal nations are governed under a different system called the “Indian Act.” Several thousand Abenaki people associated with Odanak and Wôlinak have what is known as Indian Status (Government of Canada, 2024). There are also Abenaki families living in Ndakinna who are not citizens of any of these tribes. Although all of these people identify themselves as “Abenaki,” the differences among their various locations and relations may create some confusion among outside observers.

For More Information

The sources below can help better understand the complexity and nuances of Native American recognition locally, nationally, and across North America.

Abenaki Region: Comparing Vermont’s State-Recognition Process to Indian Status in Canada

Assembly of First Nations/Assemblée des Premières Nations. (2020). What Does It Mean to Be Registered as a 6(1) or 6(2)? (p.3). Assembly of First Nations/Assemblée des Premières Nations. https://www.afn.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/02-19-02-06-AFN-Fact-Sheet-What-does-it-mean-to-be-a-61-or-62-revised.pdf

Bill Status S.222 (Act 107), Vermont General Assembly 2009–2010 Regular Session, 26 V.S.A. (Title 26: Professions and Occupations) (2010). https://legislature.vermont.gov/bill/status/2010/S.222

Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs/Gouvernement du Canada. (2018). Background on Indian Registration. Government of Canada; Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs/Gouvernement Du Canada. https://www.rcaanc-cirnac.gc.ca/eng/1540405608208/1568898474141

Government of Canada; Indigenous Services Canada. (2024). About Indian Status. Government of Canada; Indigenous Services Canada. https://www.sac-isc.gc.ca/eng/1100100032463/1572459644986

Perspectives on Indian Identity

Bergman, Gene. (1993). “Defying Precedent: Can Abenaki Aboriginal Title Be Extinguished by the ‘Weight of History’?” American Indian Law Review Vol. 18, No. 2 (1993), pp. 447-485. https://digitalcommons.law.ou.edu/ailr/vol18/iss2/4/

Hayssen, Sophie. (2021). “Tribes That Aren’t Federally Recognized Face Unique Challenges: There are almost 400 unrecognized tribes in the U.S.” Teen Vogue, November 24, 2021. https://www.teenvogue.com/story/tribes-not-federally-recognized

Hill, N. S., & Ratteree, K. (2017). The Great Vanishing Act: Blood Quantum and the Future of Native Nations. Fulcrum Publishing.

State Recognition

The Arizona Board of Regents. (2025). Governance Under State Recognition | Native Nations Institute. The University of Arizona Native Nations Institute: Founded by the Udall Foundation & the University of Arizona. https://nni.arizona.edu/our-work/research-policy-analysis/governance-under-state-recognition

Koenig, A., & Stein, J. (2008). Federalism and the State Recognition of Native American Tribes: A Survey of State-Recognized Tribes and State Recognition Processes Across the United States. Santa Clara L. Rev., 48, 79.

Ram, K. (2011). Tribal Recognition in Vermont: By Kesha Ram, Vermont State Representative the Role of Federal Standards. Communities and Banking. Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, 22(1), 7–8.

Salazar, M. (2025). State Recognition of American Indian Tribes. LEGISBRIEF: Briefing Papers on the Important Issues of the Day, 24(39). https://legislature.maine.gov/doc/5373

Featured image: Historical marker commemorating the Koas Mission des Loups. Photo by Chief Nancy Milette Doucet. Courtesy, Koasek Traditional Band of the Koas Abenaki Nation.

This article is from the traveling exhibition “Deep Roots, Strong Branches”, Vermont Abenaki Artists Association, curated by Vera Longtoe Sheehan.

© 2025. Vera Longtoe Sheehan. All Rights Reserved.

Suggested Citation

Sheehan, V. L. (2025). Acknowledging A Complicated History and Identity. Vermont Abenaki Artists Association and Abenaki Arts & Education Center.

Supported in part by

Vermont Abenaki Artists Association is supported in part by Vermont Humanities, The Vermont Arts Councill ,and NEFA – the New England Foundation for the Arts’ Cultural Sustainability program, made possible by the Wallace Foundation.

CONTEMPORARY ABENAKI ARTISTS share their artwork and family photographs in the special exhibit

CONTEMPORARY ABENAKI ARTISTS share their artwork and family photographs in the special exhibit